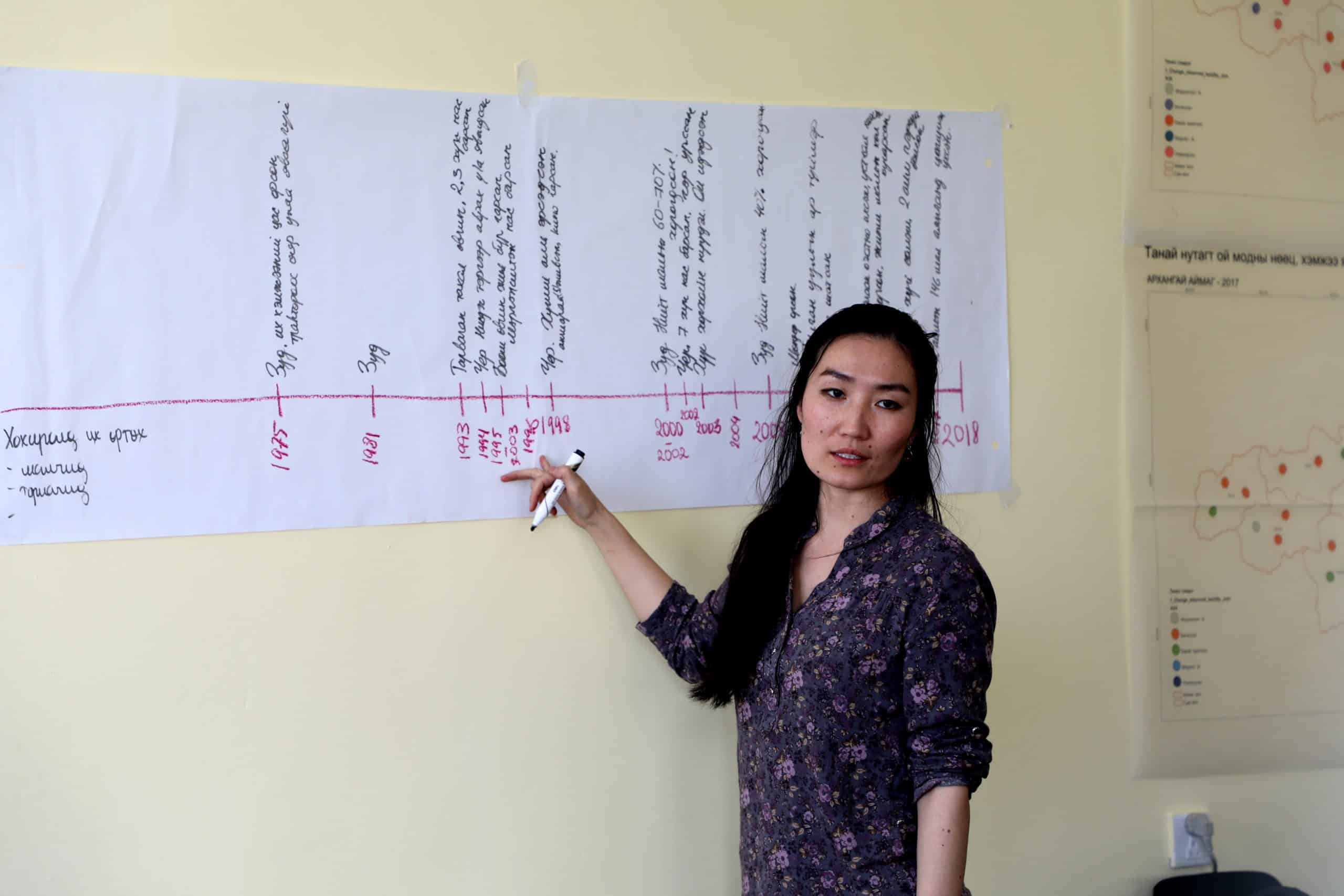

Experience: The importance of learning about gender issues when you work for an NGO

Anne recently had some training on the gender approach. She wanted to gain a better understanding of and measure the effects on gender relations of the activities she supports internationally. An initiative linked to Geres determination since 2014 to familiarize employees with inclusion in all its forms, so that it becomes an automatic reflex.

Interview and analysis.

Anne Brukhanoff

At Geres, Anne provides technical support to build the capacity of practitioners who promote entrepreneurship. She also contributes to monitoring and evaluation, skills upgrading and Geres visibility on issues related to sustainable entrepreneurship.

Anne is currently working on a multi-country programme involving Morocco, Mali, Myanmar, Mongolia and Tajikistan, which aims to encourage the rollout of sustainable energy solutions adapted to the different local markets.

Q./ Since 2014, Geres has been keen to mainstream the gender approach in its international action strategy. Can you explain to us in simple terms what this means?

A.B — Well, before 2014, we were in fact already working with women but were not fully aware of the gender dimension.

Nowadays, we see it as a strategic technical and organizational capacity we need to strengthen and renew constantly. Our entry point: women’s economic empowerment and leadership to reduce inequalities.

Q./ In practice, what forms can gender-related work with beneficiaries and Geres teams take?

A.B — We begin by raising the awareness of in-house teams so that everyone can take ownership of the concept, understand that it is a social construct which differs from one country to another, can evolve over time and also depends on each person’s perception.

Once that notion has been grasped, we work together to identify inequalities between men and women and the factors which influence and explain those gender inequalities, as well as how this gives rise to constraints on relations between women and men.

By way of example, in late 2021, we conducted a study on barriers to women’s entrepreneurship in Mali, Morocco and Myanmar, in partnership with a team of women consultants.

Read the study: Strategies for removing barriers to women’s entrepreneurship

We knew that a better understanding of the interaction between women and men within the communities with whom we work would make us better equipped to identify opportunities for improvement and activate the appropriate levers for everyone’s benefit.

Marina Dubois, Inclusion and Energy Programme Leader , talks us through these topics. She is co-building our gender strategy with the local teams and making sure that every one of us takes ownership of these notions in our various fields of work.

“Join a gender community and find allies to share good practice, experience and thoughts and support each other in tackling the huge task of mainstreaming gender in organizations and projects.”

Q./ Recently, you volunteered to get training on these inclusion challenges in the energy sector. Can you tell us about this training and your aims?

A.B — The training, provided by F3E, a learning network for solidarity and international co-operation practitioners, was designed to teach us how to “measure gender to transform practice”.

Doing this type of training was essential for several reasons:

- Above all, to boost my knowledge and contribute to the promotion of women’s entrepreneurship and mainstreaming of gender within Geres and through its operations;

- But also, to stand back from the projects I work on and to take advantage of new ideas and tools helping to improve the quality of the support I provide;

- To join a gender community and find allies to share good practice, experience and thoughts and support each other in tackling the huge task of mainstreaming gender in organizations and projects; and

- Quite simply, to go beyond gender-specific data and undertake genuine political work to try to generate change, looking closely at inequalities and current power dynamics and considering data collection systems as transformative tools.

Q./ We now know that women are still seriously underrepresented in the energy sector.

Why do you think the energy transition in particular needs to be viewed through “gender lenses”?

A.B — The issues involved in gender relations are closely connected with energy access. Adopting the gender approach means recognizing that gendered differentiation of attributes, roles and powers leads to discrimination in access to education, health and resources.

Failure to take account of women’s place, as the main consumers, suppliers or decision-makers, in the energy sector stands in sharp contrast to the weight of their domestic responsibilities and their productive activities.

Q./ What does that mean?

Can you give us an example showing clearly that it is not always easy for women to take their place in the energy sector due to the weight of the domestic duties expected of them?

A.B — Yes, of course. For example, it is the women in a household who spend the most time fetching water and collecting fuel for cooking and heating to ensure their family’s subsistence.

It may not yet be sufficiently well known but it is women again who are the first victims of the harmful effects on health of smoke emissions resulting from the use of wood and or charcoal. Why? Because women are in the majority when it comes to cooking, not men.

Finally, in the age of technology, it is important to realize that lack of access to resources and the resulting material inability to get information, combined with the absence of training for higher paid jobs, closes off all prospects of development and independence for women.

Because it is true, in quite a few countries, that women still do not have access to information.

Q./ So mainstreaming the gender approach at Geres means ensuring that we don’t contribute to increasing inequalities and, as far as possible, succeed in reducing them, is that right?

A.B —Yes, absolutely. It also means getting across the message that equal rights and responsibilities and women’s economic and political participation have positive effects for the couple, the family, the community, the country …

In the case of an NGO like Geres, action is required at all levels to take gender into account in the energy transition:

- Selecting the women entrepreneurs and building operational and management capacity;

- Involving women in the design of technology to ensure that their specific needs and aspirations are heard and that the proposed solutions are appropriate and adopted on a sustainable basis;

- Mobilizing women’s support in rolling out solutions and promoting them as decision-makers within energy projects, making sure that they not only take part but also that their voices are heard.

“Going beyond gender-specific data and undertaking genuine political work to try to generate change, looking closely at inequalities and current power dynamics and considering data collection systems as transformative tools.”

Q./ If you were to pinpoint three key aspects of gender in connection with sustainable entrepreneurship, what would they be?

A.B —To begin with, I would say that there are two sides to the gender approach:

- The first is cross-cutting advocacy. That means working to convince everyone (colleagues, partners and beneficiaries) that gender is a necessary, essential focus of our work

- The second is specific action: practical/precise activities adapted to the different operational contexts of our projects.

“If leaders and husbands come to understand that encouraging women’s economic contribution can help to boost family income, the community will adopt a positive, helpful attitude.”

Secondly, teams must clearly identify, upstream, the negative effects that their gender-related work might cause and the potential backlash (where the dominant group reaffirms its power by rejecting and acting against the dominated group) and include an appropriate strategy to prevent such effects.

Q./ What strategy needs to be adopted to deal with the potential rebound effects seen as negative by the family circle (husband, brother or just close relatives)?

A.B — Typically, a project to support women’s entrepreneurship leads to income generation for the women entrepreneurs.

This is true in Myanmar, where we are training women to become entrepreneurs marketing sustainable energy solutions in neighbouring villages with little or no access to electricity.

“The downstream solution may simply be for them to help women entrepreneurs free up time for their professional activities by taking over some of the domestic tasks.”

In some circumstances, if husbands are not involved in the venture, they may feel that their patriarchal role has been downgraded. Why? Because, if they no longer have sole responsibility for providing the household’s resources, they might have to endure, or at least they fear having to endure, their community’s disapproving looks.

If leaders and husbands come to understand that encouraging women’s economic contribution can help to boost family income, the community will adopt a positive, helpful attitude.

The downstream solution may simply be for them to help women entrepreneurs free up time for their professional activities by taking over some of the domestic tasks.

“If I manage to understand how women have succeeded in taking ownership of the training, gaining confidence and leadership capacity, well then I can say to myself: bingo, my indicator has become transformative!”

Q./ How do you see yourself now applying these gender measures in your job as technical adviser on entrepreneurial support?

A.B — I can now say that I feel stronger as an ally. I shall be able to include the tools and methodologies in the support I provide and systematize the gender approach in all my professional activities and relationships.

As someone who gives a lot of training on entrepreneurship, I think that if I simply measure parity at sessions (number of women and men present), my indicator will be gender-neutral.

Whereas if I start to measure how many women speak up during the training and to what extent they participate, my indicator becomes more sensitive and, if I manage to understand how women have succeeded in taking ownership of the training, gaining confidence and leadership capacity, well then I can say to myself: bingo, my indicator has become gender-transformative!

Read the article: Women’s entrepreneurship, a source of energy in rural Myanmar

Further reading: Women on the front line of the climate battle

Q./ Is there a lesson from the training which struck you in particular and you would like to share with us here?

A.B — That it may look simple to collect gendered data, but in practice this can easily be sabotaged by lack of time or financial resources, by a wish to take the easy way out and not risk creating tensions with operational partners.

And that the various stakeholders working on mainstreaming gender in projects need to be put in touch with each other to learn about different practices and share data collection and analysis tools.

Another point I found relevant is the need to understand how existing knowledge and lived experience can be given prominence, i.e. understanding local resistance strategies to make them as visible as the words of so-called experts and to rebalance power relations. We need to design genuinely appropriate activities and avoid imposing a Western vision of gender!

Q./ By taking this training, you in your turn become a gender ambassador for Geres.

Why do you think it’s important for employees to get a grasp of the subject? What are the positive downstream effects for an organization?

A.B — To my mind, it is vital for employees to understand gender mechanisms in their work. We can then all then think again about our focus at both professional and personal level:

- Where do I stand in public, professional and personal spaces?

- What resistance do I put up? How do I act, express myself on a day-to-day basis?

- What inequalities, violence or aggression do I suffer or cause others to suffer due to lack of knowledge, procedures or tools? Because that has an impact, downstream, on interpersonal relations in the professional sphere between colleagues and with partners and beneficiaries.

I would also say that understanding and taking ownership of the gender approach means developing consistency between the commitments/charters of values promoted by NGOs and concrete action in the field.

Resources for further study:

- In Cambodia, women are rolling up their sleeves for sustainable, legal energy

- View the conference: ” How to boost women’s empowerment in the climate battle ” (french version)

- View the video of testimony from women in Geres committed to the energy transition

- Consult the guide : “How to mainstream gender in climate projects?“

VOUS SOUHAITEZ AGIR EN FAVEUR DE LA SOLIDARITÉ

CLIMATIQUE ET SOUTENIR NOS ACTIONS ?

Dites-nous qui vous êtes et découvrez vos moyens d’action

CITOYEN·NE·S

Parce que la Solidarité climatique est l’affaire de toutes et tous, le Geres vous donne les clés pour passer à l’action.

ENTREPRISES

En tant que dirigeant·e d’entreprise, employé·e ou client·e responsable, vous avez le pouvoir d’agir au quotidien.

INSTITUTIONS & COLLECTIVITÉS

Soutenez nos actions en France et à l’international et devenez un acteur de la Solidarité climatique.

FONDATIONS

En vous engageant aux côtés du Geres, vous contribuez à la mise en œuvre d’actions innovantes et concrètes.